In the Von Kármán crater within the basin, the rover discovered iron- and magnesium-rich rock that had been ejected from the crater upon impact. The results can then be compared to the reflectance of known minerals, to see what matches.

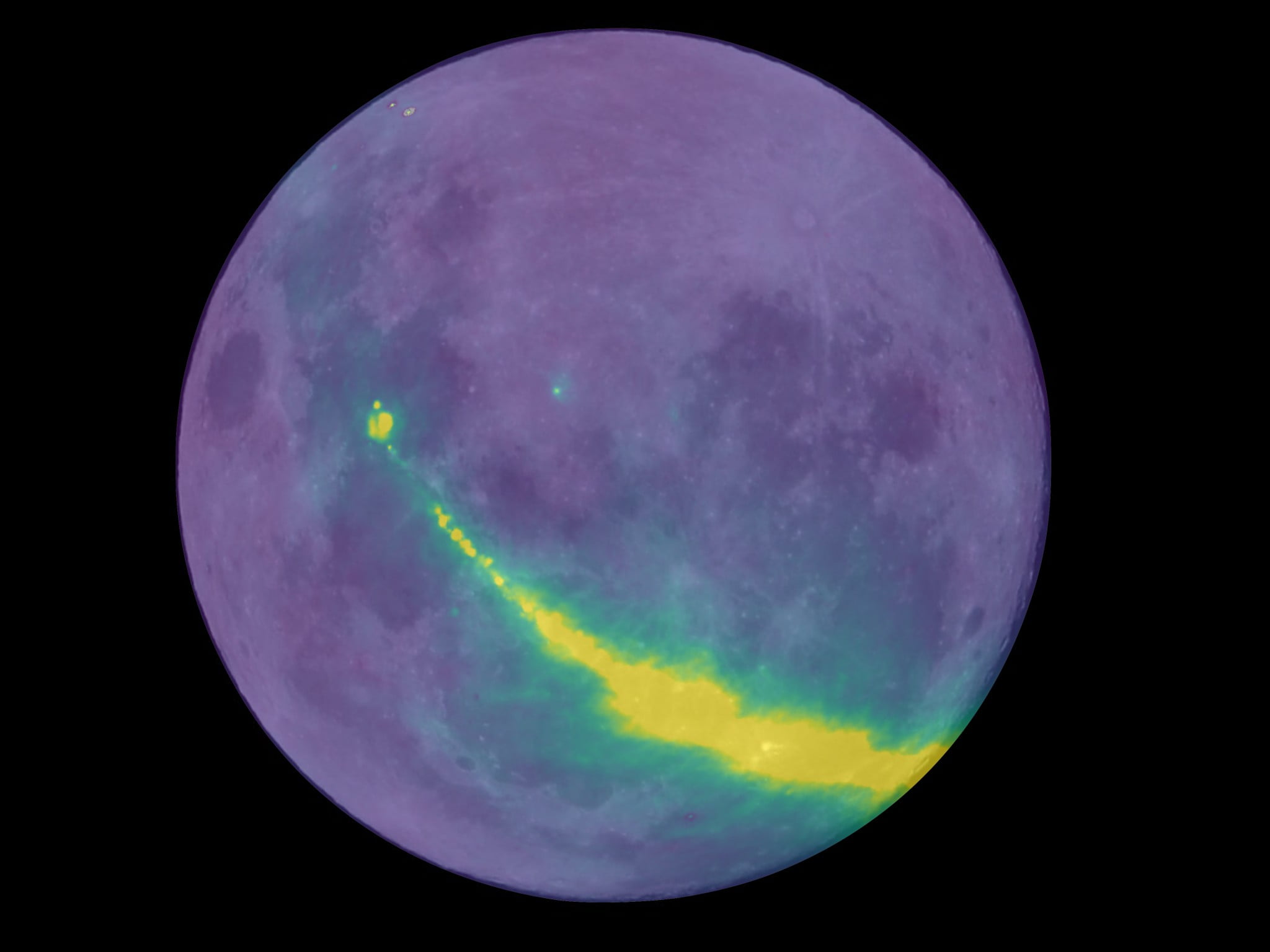

The instrument uses beams of light on the visible and near-infrared part of the spectrum to analyze the minerals in soil, collecting data on the wavelengths of light that reflects off of the material. The first results from the visible and near-infrared spectrometer suggest that the impact did just that. Researchers think that the impact that created the basin was big enough to penetrate deep into the moon's mantle and spew some of its minerals to the surface.Īnother view of the scenery around the landing site for Chang'e-4, China's lunar lander. On January 3, 2019, the lander settled down in the South Pole-Aitken, which is a whopping 1,553 miles (2,500 kilometers) in diameter and is pockmarked with smaller craters. Underneath the surfaceĬhina's Chang'E-4 lander may be changing all that. But without direct evidence of the moon's mantle composition, that's a difficult task. "It is therefore of tremendous value for understanding the evolution of planetary interiors," Pinet wrote.

Understanding this process on the moon is important, Pinet wrote, because the moon has the same three-layer structure as Earth, but without the complications caused by plate tectonics (which Earth has but the moon lacks).

In that ocean, minerals separated out by density, with lighter plagioclase rising to the top and heavier, iron- and magnesium-rich minerals sinking into the mantle. In the moon's early days, the satellite's entire surface would have been a molten magma ocean. Planetary scientists suspect that the moon formed when an enormous impact threw huge amounts of material off of the early Earth.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)